48 ADVENTUROUS YEARS

Original, independent thinking about cities and architecture

by Maurice Culot

The publishing house AAM Editions is an offshoot of the Archives of Modern Architecture (AAM), a private association set up in Brussels in 1969 to save from destruction the professional archives of late 19th century and 20th century architects.

Its objectives are to sustain interest in the architectural history of this period, make it accessible to non-specialist readers and promote an enthusiastic and active interest in it.

The story of AAM Editions, which began in the late 1960s, is inseparable from my career as an architect, professor and publisher. So here it is.

The School of La Cambre

My father built metal bridges. Admiring his work, I decided to become an architect when I was still just a teenager. My mother, who was an extremely elegant lady, introduced me to the beauty of fabrics, materials and patterns, especially those inspired by Spain, which was where she spent her childhood. Both parents supported my calling as an architect.

In 1958, I joined the Higher Institute of Decorative Arts in Brussels (aka the School of La Cambre, which takes its name from the ancient abbey in which it is housed). Founded in 1927[r2], it was run by Henry van de Velde, who designed it based on the model of the school in Weimar that subsequently became the famous Bauhaus.

This school was the fountainhead, the place where everything began. The teachers there included the architects Louis Herman De Koninck, Victor Bourgeois, Jean De Ligne, Léon Stynen, Charles Van Nueten and Robert Puttemans, the painters Paul Delvaux, Jo Delahaut and René Guiette, the graphic artists Lucien de Roeck and Luc van Malderen and the art historian Robert Louis Delevoy, author of works published by Albert Skira.

My friends and classmates included François Terlinden, Bernard De Walque, Etienne Paquay, Paul Sternfeld and Philippe Rotthier, who would go on to provide unfailing support for my future activities. It was at La Cambre that I met the painter Kris van de Giessen whom I married in 1966.

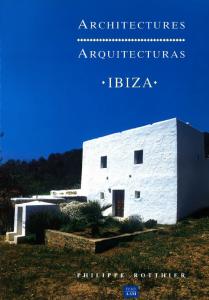

Philippe Rotthier, who settled in Ibiza in 1970, is a well-known figure in vernacular architecture. In 1982, he founded the European Prize for the Reconstruction of the City, now called the European Prize of Architecture Philippe Rotthier. [r5]In 1986, he inaugurated the Brussels Foundation for Architecture. He has written several books on traditional architecture in Ibiza, and his own works have been published by AAM Editions. In 2012, this tireless patron founded the Architecture Museum – La Loge, a centre for contemporary art and architecture housed in a former Masonic lodge in Brussels. He also supports a number of cultural associations..

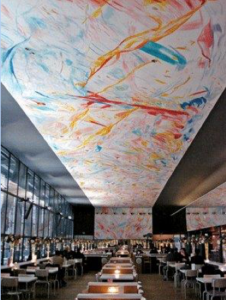

The artist Kris van de Giessen is the daughter of the Dutch Expressionist painter Arie van de Giessen and the engraver Raymonde Thys. After studying in Jo Delahaut’s studio at La Cambre, she produced monumental paintings for the Free University of Brussels (ULB), Villa Empain and Orival (together with Philippe Samyn), Philippe Rotthier and others.

The artist Kris van de Giessen is the daughter of the Dutch Expressionist painter Arie van de Giessen and the engraver Raymonde Thys. After studying in Jo Delahaut’s studio at La Cambre, she produced monumental paintings for the Free University of Brussels (ULB), Villa Empain and Orival (together with Philippe Samyn), Philippe Rotthier and others.

Her works are also in public and private collections.

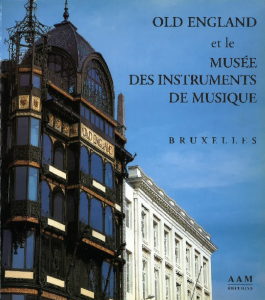

François Terlinden (1938-2007) was an urban architect who co-founded the Archives of Modern Architecture (AAM) and GUS, the architectural practice together with Danny[r3] Graux[r4]. His main achievements include involvement in creating the university town of Louvain-la-Neuve and restoring the Old England building, the Brussels Art Nouveau masterpiece that is home to the Musical Instruments Museum (MIM).

My American experience

In 1964, having gained a degree in architecture and won a scholarship from the journal Acier/Stahl/Steel[r6], I headed off to the United States. A few weeks after my arrival, I was taken on as an apprentice at Frank Lloyd Wright’s practice in Arizona, where I learnt how to draw in coloured pencil in the manner of the master and explored the archives of his legendary firm.

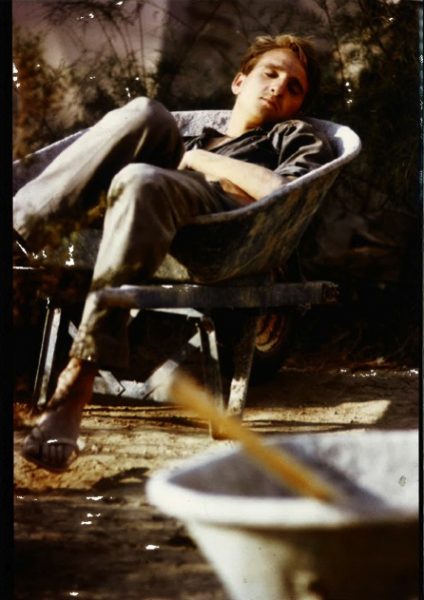

I then gained further experience under Italian visionary Paolo Soleri, one of Frank Lloyd Wright’s former students, who set up his own experimental site in Scottsdale. It was there I heard the term ‘ecology’ used for the very first time. Inspired by his example, beneath the desert’s surface I built a small house for myself that André Bloc, Director of L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, visited and was kind enough to publish in his magazine.

In 1966, I returned to La Cambre in Brussels to complete my studies in town planning. Immediately after that, together with Kris van de Giessen, who had just won a Vocation Award, we left for New York and settled in a loft in the Canal Street area and frequently visited the art galleries and Andy Warhol’s Ballroom Farm. Fired up by the sheer grandeur and vitality of New York, we returned to Brussels driven by a burning desire to DO something.

I drew on the techniques applied by Paolo Soleri to build my house close to his own. Lightly reinforced concrete was poured on the ground and the rooms were subsequently excavated. The only thing showing was the shower screen, made of a blanket dipped in plaster and suspended from a metal frame.

I drew on the techniques applied by Paolo Soleri to build my house close to his own. Lightly reinforced concrete was poured on the ground and the rooms were subsequently excavated. The only thing showing was the shower screen, made of a blanket dipped in plaster and suspended from a metal frame.

Taliesin West, Frank Lloyd Wright’s campus, was on Native American land in Scottsdale, near Phoenix, Arizona. It was 1964. Olgivanna Wright, the architect’s last wife, ran the agency. The drawing studio was covered by sheets of canvas stretched between huge wooden beams. Like my fellow apprentices, I lived in a tent pitched in the desert, surrounded by saguaro cacti and trap-door spiders.

Frank Lloyd Wright lived out in the rocky desert, Paolo Soleri on the alluvial plain, where he used the clay to make bells that guaranteed him a steady income. One of few ecologically aware architects of his day, he designed utopian cities, built half-domed concrete workshops to provide protection against the sun and made habitable structures sculpted in earth. I was like a member of a workforce similar to, but much smaller than, the people who built the pyramids in Ancient Egypt.

Antoine Pompe, a tutelary figure and new friend

Back in Brussels, in 1968 we rented a house built by Fernand Bodson at 4 rue Paul Spaak in Ixelles that had served as an artist’s studio. In one of the house’s cellars I found a drawing that was a draft design for La Populaire, a ‘house of the people’ in Liège. The drawing is 1917 and was signed by Fernand Bodson and Antoine Pompe. My life was about to change radically.

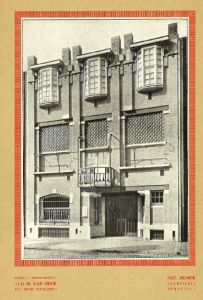

Leafing through a telephone directory I found the phone number and address of Antoine Pompe and arranged to meet him. I was 27 years old; he was 95 (and died in 1980 at the age of 107). In the course of our conversations I learnt about a whole forgotten era of architectural history in Belgium and the genius of my new friend, who in 1910 had built an exceptional clinic for Dr Van Neck, with glass brick screens built into its façade[r7].

I was determined to do whatever I could to spread the word about the work of this forgotten architect, so I suggested to the curator of the Museum of Ixelles, Jean Coquelet, that a retrospective be devoted to him. That exhibition took place in 1969 and was entitled “Antoine Pompe and the ‘Modern Effort’ in Belgium 1890-1940”.

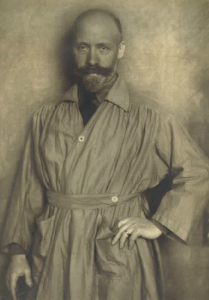

Antoine Pompe (1873-1980) was one of the first modern Belgians (along with Fernand Bodson, Leon Sneyers, Oscar van de Voorde and others) to move away from Art Nouveau and advocate a form of architecture imbued with reason and feeling. After being trained in the decorative arts in Germany, Antoine Pompe made a name for himself after building an orthopaedic clinic in 1910, then designing a number of garden cities (Roeselare and Kapelleveld) and private homes that reflected his taste for cosy ‘Gemütlichkeit’ and English domestic architecture. For a time he worked alongside the architect Fernand Bodson (1877-1966), a commanding figure who founded militant magazines like Teckné, Art et Technique and La Cité. His major works include Waterloo Farm School, an ensemble of buildings inspired by the designs of Charles Voysey and begun in 1912, and a group of three buildings built in rue Spaak in Ixelles between 1927 and 1931.

Doctor Van Neck’s clinic, built by Antoine Pompe in Brussels in 1910, reflects the influence of both Eugène Viollet-le-Duc and Paul Hankar.

Pompe retains the structural candour of Art Nouveau (using exposed metal beams in his façades and glass bricks to shield the gymnasium from sun glare[r8], bow windows in the doctor’s living quarters) and Viollet-le-Duc’s medieval rationality (air ducts behind pilasters in the façade, a metal guardrail enabling the glass bricks to be cleaned, removable ironwork on the balcony).

This design for a ‘house of the people’ in Liège, which was never built, dates from 1917 and is emblematic of the ethical mindset of Antoine Pompe and Fernand Bodson, two architects involved in the Belgian Workers’ Party and in freemasonry. Pompe and Bodson were driven by philanthropic feelings and shared their knowledge by teaching in workers’ and artistic circles.

The birth of the Archives of Modern Architecture (AAM)

When designing the exhibition on Antoine Pompe, I borrowed many documents from older architects or private owners. When the exhibition was over, the borrowers asked me what to do with all those papers that had escaped destruction, the usual fate of architects’ private archives at the time. Inspired by the archives I’d seen at Frank Lloyd Wright’s firm, I envisaged setting up a specialised private archive to collect such documents and make them available to the public. The resulting institution, founded in 1969 and dubbed the Archives of Modern Architecture (AAM), went on to be managed without interruption by Robert Louis Delevoy, who had been appointed the Director of La Cambre, and by the architects François Terlinden, Bernard de Walque and myself.

Over the years, the association occupied a number of iconic buildings: artists’ studios, a neo-Andalusian Art Deco house, a former Masonic lodge built in 1930 called Le Droit Humain, and a fin-de-siècle electricity generating station enlarged in 2000.

Between 1969 and 2017, the AAM accumulated one of the largest collections of architectural archives and put on more than 150 exhibitions, some of them itinerant.

The architects whose work the AAM has been able to present to the public include, among others, Louis Herman De Koninck, Victor Bourgeois, who had close ties with Robert Mallet-Stevens and Fernand Léger, René Braem, an erstwhile collaborator of Le Corbusier, Lucien François, Henry van de Velde and Paul Hankar.

In 1978, at the exhibition commemorating the 50th anniversary of the founding of the School of La Cambre, I met the dancer Akarova. In 1988, our ensuing friendship led to an exhibition and publication of a monograph. By way of thanks, the only Belgian artist performing modern dance at the time donated her collection of around a hundred costumes to us.

Akarova (1904-1999) was the stage name of the Brussels-born dancer Marguerite Acarin. The collection of design elements and dance costumes that she gave the AAM includes more than a hundred outfits along with their accessories, stage scenery, original LPs and photographs. Together, they constitute a unique collection of objects and documents on modern dance. The extensive monograph that AAM Editions devoted to her in 1988 particularly attracted interest from fashion icon Karl Lagerfeld, who subsequently met Akarova.

Akarova (1904-1999) was the stage name of the Brussels-born dancer Marguerite Acarin. The collection of design elements and dance costumes that she gave the AAM includes more than a hundred outfits along with their accessories, stage scenery, original LPs and photographs. Together, they constitute a unique collection of objects and documents on modern dance. The extensive monograph that AAM Editions devoted to her in 1988 particularly attracted interest from fashion icon Karl Lagerfeld, who subsequently met Akarova.

The collections feature items by more than 500 creators from Brussels, Belgium, France and various other countries, from the 19th and 20th centuries, as well as key mementos of the 1958 Brussels Expo, items from the former Belgian Congo and Zaire, the companies Blaton and Mont Blanc[r9], greenhouses, the automotive industry, railway stations, seaside resorts, cities, skyscrapers, freemasonry, Art Nouveau and Art Deco, industrial architecture and both World Wars.[r10] Among others they include works by Jos Bascourt, Marcel-Louis Baugniet, Ernest Blérot, Fernand Bodson, Victor Bourgeois, Renaat Braem, Théodore Clément, Fernand, Gaston and Maxime Brunfaut, Peter Callebout, Alban Chambon, Louis Herman De Koninck, Albert and Alexis Dumont, Jean-Jules Eggericx, Lucien François, Paul Hankar, Paul Hamesse, Georges Hobé, Victor Horta, Stanislas Jasinski, Ernest Jaspar, Léon Krier, Henry Lacoste, Marcel Leborgne, Le Corbusier, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Paul-Amaury Michel, Antoine Pompe, Léon Sneyers, Pierre and József Vago, Henri van de Velde and Frank Lloyd Wright.

The exhibitions presented by the Archives of Modern Architecture include “Brussels 1900”, “Jean-Baptiste André Godin”, “Les Châteaux de l’Industrie”, “Antoine Pompe, architecte de la raison et du sentiment”, “Louis Herman De Koninck, architecte des Temps modernes”, “Le Corbusier à Pessac”, “Rudolf Schindler”, “Victor Bourgeois”, “Renaat Braem”, “Akarova”, “Jean-Jules Eggericx, gentleman architecte créateur de cités jardins”, “Robert Mallet-Stevens” and “Joseph Bascourt”.

Diversification and activism

With the archives accumulating rapidly, the association decided to make the most of them by holding exhibitions and publishing catalogues. This led to the founding of the AAM Editions publishing house, which was constituted and put out its first books in 1969.

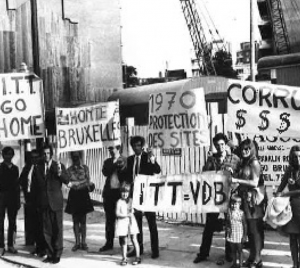

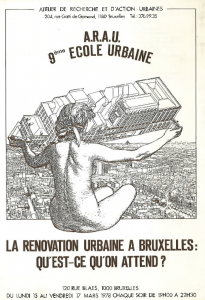

At roughly the same time, Brussels fell into the hands of speculators, who bought up much of the city. We decided to combat this wave of ‘Brusselisation’ by teaming up with students from La Cambre to carry out counter projects to be used by residents’ committees and the association of Urban Action and Research Workshops, better known as ARAU.

In 1975, the Archives of Modern Architecture won the call for tenders to produce a visual inventory of the civil and industrial architecture in the Lille-Roubaix-Tourcoing region, which led to an exhibition and two books:Les châteaux de l’Industrie and Le Siècle de l’Eclectisme. A subsequent project involved drawing up an inventory of industrial buildings in the 19 municipalities of Brussels and of various development plans.

Thus, the archives became a collection, a museum, a publishing house, a documentation centre and an active protagonist in the urban protest movement.

‘Brusselisation’ was a term coined in the 1960s to describe the process of the peacetime destruction of a city by private and public developers, policymakers, architects and engineers who teamed up with the most shamelessly speculating companies against the interests of the general public and urban heritage.

In 1978, AAM Editions published Rational Architecture by Léon Krier, the first book devoted to the reconstruction of the European city. Another success followed in 1980: the first monograph devoted to Robert Mallet-Stevens. In 1986, François Loyer’s work on Paul Hankar was the subject of a monumental publication, La Goutte d’Or, Faubourg de Paris, co-published in 1988 with the publisher and author Eric Hazan, which was a plea to save a popular district brutally renovated by the French State and the City of Paris. Now a friend, today Hazan runs the La Fabrique publishing house. Penser la ville by René Schoonbrodt and Pierre Ansay (1989) became a frequently republished reference work, as did Hélène Guéné’s bestseller,Odorico, mosaïste Art Déco.

The Carrés AAM collection showcases the work of Victor Horta, Paul Hankar, Henry van de Velde, Le Corbusier, Fernand Bodson and Antoine Pompe, Akarova, Pierre Barbe, Marcel Leborgne, Antoine Courtens, Jean-Jules Eggericx, Henri Sauvage, Robert Mallet-Stevens, Jean-Baptiste André Godin, Jozsef Vago, Frank Lloyd Wright, Eliel Saarinen, Henry-Jacques Le Même, Renaat Braem, Andre Jacqmain, Leon and Rob Krier, Andres Duany, Rudy Ricciotti, Jean Nouvel, Marcel Broodthaers, Panamarenko, Victor Bourgeois, Jos Bascourt, René Braem, Antoine Courtens and others.

The company also publishes historical works and books on theory (Les Bastides, essai sur la régularité, Forme et caractère de la ville allemande, Berne et les villes fondées par les ducs de Zähringen, La Cambre 1928-1978, Lettres de Sicile), books on art and photography (Intérieurs by François Hers, Lions de Paris by Didier Serplet,Fleurs de Paris by France de Griessen) as well as books on Art Nouveau, Art Deco, industrial architecture, student housing, comics, fashion, housing, sustainable development and other topics.

The aim of the counter projects devised by the Archives of Modern Architecture and students from Maurice Culot’s architecture workshop at the School of La Cambre was to propose realistic alternatives to destructive private and public projects. Designed to be easily interpretable by the general public by focusing on axonometric views and perspectives, they are drawn in keeping with the ‘clear lines’ of Belgian comic books to make them easily reproducible in black and white in newspapers. Today these counter projects are arousing renewed interest and it is instructive to consult the recent studies that have been devoted to them, particularly by the art historian Isabelle Doucet.

The Research and Urban Actions Workshop (ARAU) was set up in 1969 on the initiative of the sociologist René Schoonbrodt, the lawyer Philippe de Keyser, the theologian Jacques Van der Biest and the architect Maurice Culot to analyse private and public projects and criticise those that were detrimental to the city and quality of life of its inhabitants. It publicises its positions in press conferences and sometimes by undertaking spectacular actions with a humorous touch. ARAU’s actions proved decisive in democratising the decision-making process in Brussels and putting an end to ‘fait accompli’ urban planning. ARAU is still active today under the leadership of Isabelle Pauthier, and it also organises critical city tours of Brussels, study trips and an annual urban school focussing on topical issues. ARAU’s activities are often relayed by AAM guides, posters and publications. ARAU’s slogan is “The city or nothing”.

Towards international recognition

Today, the unusually wide-ranging activities of the Archives of Modern Architecture command international attention. Distributed in France by Le Moniteur and in the United States by Princeton University Press, AAM publications are gaining in popularity.

Inspired by the bulletin published by the AA School in London between 1975 and 1990, the AAM magazine La Revue AAM helped to expand AAM’s audience by calling on European and American contributors and defending the idea of anti-industrial resistance, which was swimming against the current at the time.

In 1969, I started teaching at La Cambre. This provided another opportunity to engage in exchanges and link up with fellow teachers and professors at European and American schools.

In 1979, I was invited to join the team of the French Institute of Architecture (IFA) and run its History and Archives Department. So in the early 1980s Kris, my two children and I moved to Paris.

At the invitation of Léon Krier and Paolo Portoghesi, the Brussels counter projects were exhibited at the first Venice Architecture Biennial in 1980.

In 1982, the European Prize for the Reconstruction of the City [r11]was created in 1982, followed in 1986 by the Brussels Foundation for Architecture. I preside over both these two internationally recognised militant initiatives initiated and sponsored by Philippe Rotthier.

In the 1990s, I was invited to teach at Prince Charles’ summer school in England, and the practice of counter projects was applied, this time with the agreement of the respective mayors, in Oxford, Viterbo, Biarritz[r12] and Chinon.

Presentations of the AAM’s work and the projects of my students at La Cambre were printed in renowned journals including Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, Lotus International, Oppositions, Architectural Design and Macadam, among others.

In 2000, I resumed my activities as a private architect, working for the Parisian agencies Styles Architectes and Arcas-Paris, which opened up fresh editorial opportunities.

In 2002, I created the ‘Petits carrés’, a collection of small, 64-page, pocket format books whose content is between article and book length. So far 30 titles in this collection have been published.

In 2003, the AAM started co-publishing the books produced by the agency Ante-Prima run by Luciana Ravanel, a former Director of the French Institute of Architecture (IFA). Most of these works are by contemporary French and European architects and landscape architects (including Rudy Ricciotti, Jean-Baptiste Pietri, Alfonso Femia, Roland Carta, Chaix and Morel, Michel Pena and others) devoted to topical issues, such as modern railway stations, the sustainable city, French architects around the world, etc.

Ten years after entering the School of La Cambre as a student, I returned as a teacher, borne along by the events of May 1968, the success of the exhibition ar the Museum of Ixelles and the creation of the Archives of Modern Architecture, which resulted in me and my friend François Terlinden being awarded a Vocation Award by Françoise Giroud.

With London and the AA School run by Alvin Boyarski at the forefront of developments in architecture, Paris was not lagging far behind, thanks to the towering figure of Bernard Huet, manager of L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, who dedicated the magazine’s first cover to the AAM. Exchanges of exhibitions and interinstitutional conferences, moving from capital to capital, punctuated life at La Cambre, giving me the opportunity to invite a host of creative minds, many of whom would become friends: the architects Fernando Montes, Antoine Grumbach, Colin Fournier, Claude Parent, Charles Vandenhove, Roland Castro, Peter Cook (who introduced me to Léon Krier, marking the start of a long and enduring friendship punctuated by projects, conferences and books), the filmmaker Jacques Baratier, the historian Henri Guerrand, the playwright Jean Louvet and many others. This circle of friends extended to Switzerland with Jacques Gubler, to Austria with Rob Krier, to Italy with Dario Matteoni in Pisa, Pierluigi Cervelatti in Bologna, Pierluigi[r13] Nicolin in Milan, who runs the magazine Lotus International, to the United States with Thomas Gordon Smith and later Andres Duany, Roberto and Rosario Behar, François Lejeune, Lucien Steil, Bob Stern and more.

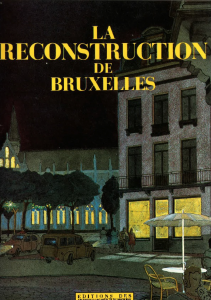

Very soon, the terrible destruction to which Brussels had been subjected by politicians, developers, architects and engineers prompted me to get the students working on counter projects that the association of Urban Action and Research Workshops (ARAU) and local residents’ committees used in their struggle against Brusselisation. In a number of publications (Le Bateau d’Elie, La tour ferrée, La reconstruction de Bruxelles and others), AAM Editions reported on this tumultuous period, which is today the subject of research and exhibitions.

Published until 1990, the magazine was a medium intent on making the most of European cities and served as a platform for some iconoclastic editorials, a few of which were reprinted in other publications. One such example was the article I penned with Leon Krier entitled L’unique chemin de l’architecture, which also appeared in the American magazine Opposition. Most of the first covers were illustrated using specially commissioned works by the artist Rita Wolf.

In 1979, I was invited to join the team of the French Institute of Architecture [r14](IFA) and run its History and Archives Department. I had been recommended by François Mathey, Chief Curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts, who in 1971 had entrusted me with the sections on Victor Horta and Henry van de Velde in an exhibition on pioneering 20th century architects entitled “Pionniers du XXe siècle”.

In 1980, the French Institute of Architecture (IFA) was housed at 6, rue de Tournon, in the 6th arrondissement of Paris. During the period when I was active there – from 1979 to 2005 – it was successively headed up by Francis Dolfuss, Florence Contenay, Luciana Ravanel and Jean-Louis-Cohen, with its various departments run by François Chaslin, Jean-Pierre Epron, Bertrand Lemoine, Patrice Goulet and myself. My contribution entailed setting up archives of 20th century architecture for the IFA. Kept in a former hospital, they constituted an unprecedented collection in France of French architects’ private archives.

At the time, Le Moniteur and Mardaga, run by Pierre Mardaga and Maité Hudry from Editions Norma, were the main publishers of books conceived as collections, which included “Villes”, “Architecture”, “Architectures des années 20 et 30”, “Essais” and “Villes de la frontière”, co-published with the Interministerial Delegation for Territorial Development and Regional Attractiveness (DATAR). The stand-out books published at the time included the monumental publication Journal de Fontaine, the first monograph on the architect Pierre Barbe by Jean-Baptiste Minnaert, a monograph on Jean-Charles Moreux by Susan Day and a work on Edouard Niermans by Jean-François Pinchon. Attention then turned to the particularly fragile coastal, spa and climate architecture, resulting in the publication of books on the Ville d’Hiver area in Arcachon, the seaside resort of Hossegor and the architecture of the Basque, Normandy and Opal Coasts. Thanks to support from the Ministry of Culture and Christian Dupavillon, these books helped to protect the heritage of private buildings underrepresented in the history of architecture. The art historian Bruno Foucart was actively involved in this campaign, contributing much written material and involving his students at the Sorbonne in the work.

In 2000, the IFA merged with the Cité de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (City of Architecture and Heritage) and moved into the Palais de Chaillot.

In 1982, the architect Philippe Rotthier founded the European Prize for the Reconstruction of the City, now called the European Prize of Architecture Philippe Rotthier[r15], entrusting its organisation to Léon Krier and Maurice Culot. This triennial award aims to promote lasting achievements not generally reported on by the professional media and which fit into local contexts and reflect historical continuity.

The juries comprise people from very different professional backgrounds. The recipients of the prize can be architects, like Quinlan Terry, Manzano Monis, El Wakil or François Spoerry, but also historians such as Eusebio Leal Spengler, the man in charge of restoring Old Havana, film makers like Emir Kusturica or even institutions and municipalities.

The Brussels Foundation for Architecture was founded in 1986 by Philippe Rotthier to be the AAM’s showcase and to organise the European Prize of Architecture Philippe Rotthier. Very quickly, under the leadership of its successive Presidents and Directors (Caroline Mierop and Bartomeu Mari, Diane Hennebert and Anne-Marie Pirlot), the Foundation started holding a wide range of events (exhibitions, concerts, major conferences, debates, etc.), making it one of the most important cultural venues in Brussels. People could go there to listen to and meet architects like Norman Foster, César Pelli and Rem Koolhaas, writers like Raoul Vaneigem, film makers like Amos Gitai, artists like Panamarenko[r16], Matt Mullican[r17] or Judith Barry. In 1989, the Foundation launched a call for young European architects, which in 1995 led to the reconstruction of part of rue de Laeken in Brussels. In 2000, under my presidency and the direction of Anne-Marie Pirlot, the Foundation started focussing its activities on raising children’s awareness of art and architecture.

Founded in 2000 by Bart Chielens and Maurice Culot, the agency Arcas Paris specialises in the construction of new quarters in the classical, Art Deco and Modernist styles. It is also involved in book production. For example, in 2017 the architect Bernard Durand-Rival and Maurice Culot published Val d’Europe Vision d’une Ville to mark the 30th anniversary of the creation of the only new French city built according to the founding principles of European cities. That same year, the restoration of the Banque de France site in Asnieres-sur-Seine prompted the publication of a beautiful book on the architectural heritage of this Art Nouveau and Art Deco conurbation near Paris. William Pesson, the architect, art historian, President of the Quatremère de Quincy Association, specialist in esotericism and partner of the agency has published his essays in a new collection including Architectures maçonniques, Architectures Rosicruciennes, and soon also Architectures théosophiques.

Saving what we have to enable better publications

In 1998, concerned about the future of the collections managed by the AAM, I suggested to Minister Hervé Hasquin, a professor and man of culture, who is currently the Permanent Secretary of the Academy of Belgium, that somewhere be set up to gather together the activities of various cultural associations and serve as a home for the collections of the Archives of Modern Architecture. This resulted in the creation of an organisation called the International Centre for City, Architecture & Landscape (CIVA). An international competition was arranged and won by a French team led by Jean-Philippe Garric. A new building was constructed as an extension to the old electricity generating station that the Brussels Foundation for Architecture had occupied for 20 years in rue de l’Ermitage in Ixelles. It was inaugurated in 2000.

Moving into new, purpose-built premises further enhanced the reputation of the AAM, which over the years has become a real public service, albeit one lacking both financial resources and staff, the AAM team being highly competent, but rather small. The association duly considered a number of scenarios for ensuring the continuation of its activities: relinquishing some of its collection to a renowned foreign institution (Centre Pompidou, Getty Foundation, the Canadian Center for Architecture (CCA)); dispersing items between various Belgian institutions (the Royal Library, Belgian National Archives, the Museum of Modern Art); selling off part of its collections, and so on. But the Board of Directors deemed none of these options satisfactory, because it wanted the heritage not to be dispersed and to remain in Brussels.

A solution that ticked all the right boxes and was therefore quickly accepted came in 2016 when the Brussels-Capital Region offered to acquire all the collections, valued at €20 million, and to retain the staff, for a symbolic sum of €1.

Since the publishing house, a personal initiative which I had always run and where I had made the editorial choices, was not included in the donation, it retained its independence. Thus, the private cultural adventure embarked on nearly 50 years ago by a handful of architectural activists goes on.

AAM Editions today

Today, the publishing house AAM Editions, disseminated by Entrelivres and distributed in Europe and Canada by Les Belles Lettres Diffusion Distribution [r18](BLDD), is more actively than ever pursuing its publishing activities aimed at an international readership, especially in France, as evidenced by its recent publications which include Fleurs de Paris in the collection “L’ame romantique d’une ville” (The Romantic Soul of a City) managed by the multidisciplinary artist and author France de Griessen.

My involvement in urban battles, my passion for Art Nouveau, Art Deco, the Viennese Secession style and coastal architecture have led me to contribute to numerous publications, magazines and books. Today, I am a director of the militant magazine Monts 14 which is fighting against developments that threaten to ruin the beauty of Paris. Recently published favourite texts of mine include my contributions to the book Portfolios Modernes et Art Déco published by Editions Norma in 2014, to the monograph on the first writings of Robert Mallet-Stevens between 1907 and 1914 (AAM Editions, 2016), to Modernes Arcadies, co-authored by Bruno Foucart (AAM Editions, 2017), Asnières-sur-Seine, Art Nouveau Art Déco, co-written with Milena Charbit (AAM Editions, 2017) and In the Mood for Architecture, Tradition, Modernism & Serendipity by Lucien Steil, to be published by Wasmuth in 2018.

Over the years, a great many authors, historians, artists and photographers have placed their confidence in AAM Editions, including Robert Louis Delevoy, Roger-Henri [r19]Guerrand, Jacques Gubler, François Loyer, Annick Brauman, François and Luc Schuiten, Philippe De Gobert, Gilbert Fastenaekens, Bruno Foucart, Philippe Rotthier, Anne Van Loo, Francis Strauven, Yves Marchand and Romain Meffre, François Hers, Sophie Ristelhueber[r20], Philippe Panerai, William Pesson, Jean-Baptiste Minnaert, Katia Pecnik, Mark Dachy, Harold Zellman, Jean-Paul Midant, Jean-Louis Cohen, Lucien Steil, Roberto Behar, Monique Eleb-Vidal, Louis Chevalier, René Schoonbrodt and Giovanni Wieser